Of

the former Soviet Republics in Central Asia, Tajikistan is the

smallest and poorest. It also served as the Russian invasion ground

for Afghanistan in 1979. A large number of Tajik men subsequently

died in the failed, drawn out war. The lingering effects of the

fighting combined with the problem of the country's ethnically

diverse population led to instability following independence in 1991.

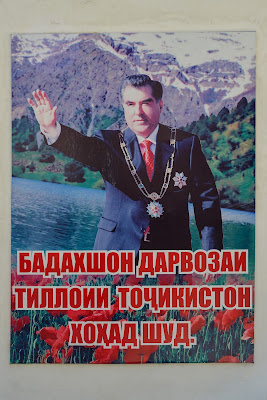

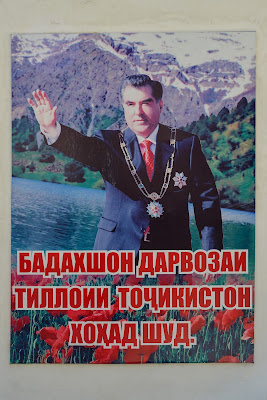

Civil war erupted, and after two years, a new president elect named Emomali Rahmon ended the fighting. He later succeeded in maintaining peace and is now seen as a national hero. Ubiquitous

posters of the man emblazon the entrances of schools and other public

buildings. In them Rahmon has his hand raised high, while at the

bottom, boldly written words promise progress and growth.

During

my time in the region, Tajikistan was the third and final country I

visited. Kazakhstan and Kyrgyzstan which I'd traveled to first seemed

quite similar to one another in terms of the people and culture.

Tajikistan differed in that its history was shaped more by Persian

than Turkic influence. This became most evident in the languages

spoken. Tajik was mutually intelligible with Farsi, while Kazakh and

Kyrgyz had more in common with Turkish. The people in Tajikistan also

acted with greater Islamic conservatism. The

women covered their hair and a larger percentage of the men grew

beards. Moreover, I got the impression that they did not identify

much with Russian culture and the younger generation preferred to speak English over Russian. I could understand why. The legacy of the Soviet years was not a good one with the memory of the

Soviet-Afghan War still fresh on their minds. But I digress. Let's see how my time in the country went.

|

| National Flag |

Border Crossing

Tajikistan lies south of Kyrgyzstan,

the country from which Calvin and I entered. There were two access

points. We chose the eastern one that crossed via the Pamir Highway.

The road led past a range of mountains including Peak Lenin, a 7135m

monstrosity split between the two countries. From there we needed to

deal with the immigration checkpoints. Oddly a tract of 20km

separated the Kyrgyz checkpoint from the Tajik one. Since we'd gotten

proper visas at an embassy beforehand the immigration officers let us

through without hassle and the other passengers in our taxi were locals.

From the border the unpaved Pamir Highway wound up a 4282m pass and

altitude sickness became a factor. It subsided as we came down the

opposite side, and an hour or so later we stopped at Kara-Kul, a deep

blue lake surrounded by high mountain peaks.

Kara-Kul village, on the eastern side

of the lake, was a place that seemed to exist at the edge of the

world. The village had one of the raunchiest public toilets I have ever

used. It was a little hut with three holes lined up on a cement

floor. The glaring problem was the lack of partitions. The toilet

also reeked of ammonia from the piss, a stench so strong my eyes

watered over. When I came out the stop provided time enough to size

up the small village. White mud structures fed down to the shore with

a single mosque sticking out from the bunch. The only sign that the

village was somewhat connected to the rest of civilization was the

line of electricity poles that ran in and out along the highway. The

Soviets had built the road in the 1930's for military purposes and it

had since become the lifeblood of the mountainous land. Large

commercial trucks now plied its entire length, many of which came

from Kashgar in western China. Otherwise vehicle traffic was scant

and limited largely to 4WD vehicles that could handle the dirt and

mud. Our taxi, a Toyota Landcruiser, took us as far as Murgab.

Murgab was essentially a larger

version of Kara-Kul village. There were more buildings, more people,

a small bazaar, and even two gas stations. But Murgab still had that

dusty, worn down look of an Old West town. The whole Pamir region was

as remote and desolate a place as I'd visited. It covered about half

the country of Tajikistan with less than 5% the population living

there. Murgab was one of its few real towns. After we arrived, Calvin

and I checked into its one hotel. The interesting thing was, we

didn't get a room. Instead we pitched our tent out front for two

dollars and could still use the hotel's amenities such as toilet and

shower. A surprising amount of other tourists had also made a stop in

Murgab. They were cyclists pedaling down the Pamir highway, simple

backpackers like myself, motorcyclists, groups on a rushed tour, and

perhaps most interesting, men participating in the Mongol Rally--a

charity event that had participants drive 10,000 miles from London,

across Asia, through Mongolia, and finally to Ulan Ude in Russia.

These participants had roughly a month and a half to do it and they

didn't linger long in town. The men crammed back inside their

vehicles and sped north leaving a swirl of dust behind.

|

| Shared Taxi |

|

| Mosque in Kara-Kul |

|

| Near the Lake |

|

| Passanger Gives a Kiss |

|

| Northbound Road Sign |

|

| Murgab Mosque |

|

| Kids Fooling Around |

Shared Taxi

In Murgab, Calvin and I had one simple

objective. We needed to find four other travelers so that we could

hire a shared taxi to take us to Khorog at the other end of the Pamir

Highway. Our search took an entire day and produced the following

members--Stefan, a German investments auditor, age 32; Ada and

Matilde, two French medical students, ages 24 and 25; and Aurelie, a

Belgian school teacher, age 32. Once assembled we formulated a plan.

We would travel a day down the Pamir and then take a side route to

Khorog along the Wakan Valley, a distance of some 480km. Next we

asked around for a vehicle and driver. The receptionist at the hotel

put us in contact with a local guy named Musa. That same night we met with

him and negotiated a price for the journey. Because we didn't want to

rush we decided on 5 days with several stop offs along the way, a

trip which came to $65 per person for the transport. This was the

only choice we had because no public buses ran on the Pamir Highway.

Then again, I suppose we might have tried hitchhiking, but that

would've meant we'd have to pass up a lot of sites on the way, and

the whole nature of it would've been unreliable, likely including

long waits in an area known for sparse vehicle traffic. So it was

settled. The next morning we gathered at 9:00AM in front of the

hotel, loaded up the 4WD Mitsubishi Pajero, and soon embarked.

Day one took us through mostly a wide

valley with peaks at every horizon. For lunch we stopped beside a

clear pond full of fish. At the adjacent restaurant they served us

the same type of fish, though the proprietor told us they were not

from the pond, but rather a nearby river. The fish were the small

bony type--deep fried and entirely edible. I still removed the bones.

After that we made for Yashil-Kul, an iceberg colored lake that was

not as cold as I'd imagined it might be. So I went for a swim.

Normally, I would have splashed around like crazy, but this time I

had to take it easy because the high altitude quickly had me short of

breath. None of the others joined me. Their loss. We would not have a chance to wash off again until the following night. Our guesthouse,

which we went to later, was as simple and barren as the surrounding

village of Bulunkul. Like elsewhere in the northern Pamir, the people

were ethnically Kyrgyz, and very Eurasian in appearance. Most

striking were the eyes. The guesthouse owner's daughters had ones with greenish, grey irises highlighted by black

edges. Not camera shy, the two gladly posed for pictures as I snapped

away like a Hollywood paparazzo. I wondered if past visitors

traveling the Pamir had done the same. If so, the girls were used to

the attention. Later that night I took out my Nikon again to shoot

the stars. The cold and moonless sky made for excellent photographic

conditions as I captured the Milky Way overhead. The others tried as

well, but their inferior cameras produced noisy, worthless images. In

the end I gave them copies of mine.

|

| Clear Pond |

|

| Fried Fish |

|

| Kyrgyz Girls |

|

| Starry Night |

|

| Musa Fixes the Pajero |

|

| Open Highway |

The second day of the journey led us

off the Pamir Highway and onto an even more rugged road along the Wakan

Valley between Tajikistan and Afghanistan. At the last checkpoint

before entering the area we took photos with the bored military men

manning the post. One of them let Matilde hold his AK-47 rifle. Then

we continued on through the remote and sparsely populated land, a river

marking the border beside us. The people in the valley were Tajik,

but spoke their own language, and moreover, followed the Ismaili

Islamic faith. Elsewhere in the country the people were predominately

Sunni. As a sign of their religious beliefs, the locals had a living room with a kind of sky light made of concentric squares and

five pillars holding up the ceiling. Of the five pillars one

represented the Prophet Muhammed, and another his first wife. As the

days passed we went from one guesthouse to the next. The

accommodation at these places included dinner, breakfast, and

sometimes, a hot shower. We also went to the ruins of Yamchun Fort,

a once mighty structure that had guarded an old Silk Road route into

China. A kilometer from the fort was a hot spring called Bibi Fatima.

The facility had a large building with separate indoor pools for men

and women. On our side, Calvin, Stefan, Musa and I enjoyed a dip in

the hot water. A Japanese tourist later popped his head in and

started taking photos while we were sitting naked. He then left, just

as fast as he'd entered. On the other side Ada, Aurelie and Matilde

shared their pool with a dozen Tajik women of various ages. They

later told me the local women had shaved their pubic hair. That was some

real food for thought.

The road continued along the

Afghanistan border and the further west we went, the more villages we

saw on both sides of the border. The Tajik side, however, was far

more developed. Towards the end there were towns with multi-storied

buildings, paved roads and traffic signals. Otherwise the people

lived in scattered houses surrounded by greenish-yellow barely

fields. Finally, on the fifth day we arrived in Khorog. It was the

first proper city I saw in Tajikistan, and as was the case with the

other Tajik cities I'd later visit, I took an immediate liking to the

place. Not that Khorog had anything interesting to see or do. The

city's charm came instead from its pleasant atmosphere and vibrant

people. That and there were many restaurants that offered a wide

variety of dishes on the menu. Since I'd entered the country, food

had been so limited, and now I had access to real stuff like pizza and ice cream. Moreover, I could use the Internet for the

first time in a week. Khorog, in short, was the perfect place to

recharge and prepare for the journey ahead.

|

| Matilde and AK-47 |

|

| Out to Dry |

|

| Tajik Instruments |

|

| Yamchun Fort |

|

| Graffiti |

|

| Old Ladies |

|

| Meal at Guesthouse |

|

| Rahmon Poster |

|

| Khorog Bazaar |

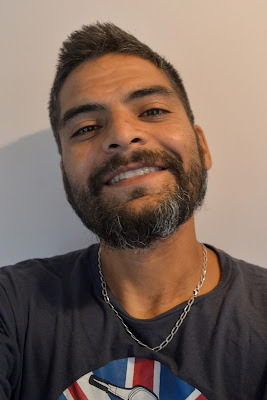

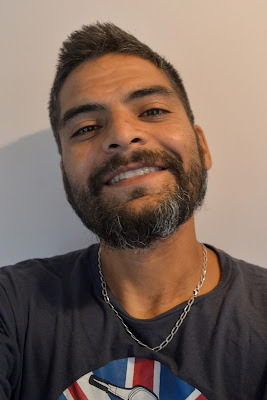

Travel Beard

I remember learning about Sigmund Freud

in Psychology 101 at university. Now, over ten years later, the only

knowledge that remains is his theory of penis envy. How could I

forget such a thing? Freud postulated that women envied a man's

penis, and boys likewise envied the size of their father's penis.

This somehow influenced people's behavior. I suppose I too had a bit

of the penis envy complex growing up, especially after I started

watching pornography. But as time passed I started to care less that

I didn't have a huge package, and worried more about other physical

shortcomings. Most troubling was the size of my hands. The palms are

fine, but the fingers are short and slender. This means I never had

any hope at becoming a pianist (not that I ever harbored such

aspirations). The real problem I experienced was in sports. I

couldn't palm a basketball in high school gym class, and while

wrestling I had a harder time grasping an opponents wrist.

I'm sure everyone has something they

would physically change about themselves. Apart from my hands, maybe

I could be a little taller. And I'd change my facial hair too. I can

grow a mustache and a bushy goatee, but having a proper beard is

another matter. When I go unshaved for a long while little patches of

uneven hair still remain on the sides, and they detract from the

symmetry and overall gravitas that a good beard should represent. So

those parts I shaved. This was how it's always been and I was fine

with it, at least until I started traveling. I met a lot of other

tourists after leaving Japan, some of whom had big scruffy beards.

This was because they'd chosen to forgo shaving as one month on the

road led to another. When I saw these beards a pang of envy jittered

in my gut. I too wanted a travel beard, and after 8 months of

encountering them at every backpacker hostel I visited, I'd had

enough. It came time to grow one of my own. I no longer cared how

terrible it looked.

In total I needed about 60 days before

the beard grew thick enough to cover the gaps. I was half way through

Tajikistan at the time, and as I walked the high mountains, my beard

quivered in the cool, invigorating wind. Never before had I

maintained my facial hair for so long. In a primal way, I felt as if

I'd finally become a complete man--the total package. The genuine

article. Moreover, my beard was now more than simply an extension of

my person. It'd taken on a life of its own. And I had no intention of

shaving it. The beard will grow with me while I continue my world

travels. The thought excites me. I want to know how long it can

become, and if it'll give me the same air of manliness as say, Freud,

Abe Lincoln or Chuck Norris. I look forward to finding out.

|

| Hairy Face |

Hitchhiking

Slowly but surely, my impression of

Tajikistan became that of a country defined by one long road. At

least in the eastern part. Two main roads were the only means to get

to the capital of Dushanbe. After Khorog I opted to take the southern

route. At first I was with Calvin, Matilde, Ada and Aurelie. Stefan

had rushed ahead by shared taxi, leaving us behind. Then it was only

two of us because the others wanted to do a hike in the Jizeu valley.

I didn't feel up to it and instead headed to the capital with

Aurelie. To save money we gave hitchhiking a go. We didn't have much

luck at first. Perhaps we covered 70km after a day. This was not

good. 650km still stood between us and Dushanbe. On the bright side

we met a local woman who invited us to stay at her family's home. She

cooked for us as well, serving up a soupy platter consisting of

tomatoes and potato. The woman, Tajimisso, said she liked English,

and hoped to one day study in London. A cousin of hers already lived

there. It seemed many Tajiks relocated abroad, though most went to

Russia where they could easily get a work visa.

On the second day, we awoke early and

had tea and bread for breakfast. Afterwards, Tajimisso helped us flag

down a truck. The driver was en route to Dushanbe. He said Aurelie

and I could join him, so we climbed into his 12-wheeler. The Shacman

truck, I quickly realized, did not have good suspension for the

unpaved road, and as a result, it was slow going the entire way.

After a while I felt as if seated on an old, rickety carnival ride.

As for Aurelie, she'd become sick while on the Pamir Highway, and the

motion of the truck didn't do her upset stomach any good. More than

once she asked the driver to stop so that she could do her business

on the side of the road. On another occasion we had to pull over

because of a flat. The driver got out to remove the tire from the

truck and replace its inner tube, a laborious task that took over an

hour. Then, later in the evening we had a second flat. Because it

was a bolt that had punctured the tire, the driver needed to patch

the hole before putting everything back into place. It had become

dark by then and I helped by holding a flashlight. While watching, I

thought the task didn't look too different from the repair job on a

bicycle tire, except for it being on a larger scale. In any event,

the flats really slowed us down. By the time we stopped for the night

we were no where close to Dushanbe.

|

| Road to Dushanbe |

|

| Tajissimo and Aurelie |

|

| Flat Tire |

|

| At the Wheel Again |

|

| Another Truck |

|

| Lunch Time |

On the third day our luck did not

improve. Two other flat tires brought us to a halt. The driver

couldn't believe it for the last one. He beat the steering wheel,

cursed aloud and shook his head. I felt really bad for him. At the same time I wondered how we could get so many flats. It was then the

driver said he was carrying a heavy load of statues from China which explained why the tires kept giving out. And our mechanical

difficulties weren't the only thing keeping us from Dushanbe. We had

to make additional stops at road checkpoints and came to about ten of

them Each time the armed guards wanted to see our passports. The

driver also handed over a 5 somoni bill (about a dollar) before

passing through. Because he slipped it into their palm I'm pretty

sure it was some kind of bribe. Then there were the stops for food.

Aurelie who wasn't feeling good could hardly eat a thing. In the

meantime I was trying to look after her, giving her medicine and what

not. For a while the driver thought we were married. He then told us

with a smile how he had two wives. Apparently, it was acceptable in

Tajikistan to have up to four. I joked with Aurelie that if I had

that many wives I'd probably kill myself. Hell, the stress from one

relationship might be cause enough. Aurelie didn't find my comments

funny. If anything, she pitied the women who became someone's second

wife. I shrugged and drank my tea. Such was the Muslim world.

We arrived in Dushanbe late. Very late.

It was past 2:30AM, and since the driver was not headed to the city

center, he dropped us off where there were still taxis. It was an

area with bars and nightclubs. A taxi driver approached us, asking

for a lot of money to take us to a hotel. We had no idea of the

distance and didn't see the point of paying for a room, not if for

only a few hours. The alternative was to make use of my tent in a

nearby park. Still close to the road, we heard drunk men coming out

of the nightclubs. A few got into an argument which frightened

Aurelie. I assured her everything would be alright. And it was. After

a bit of sleep, we rolled up the tent, took a microbus to the center

and found a hotel. Next, I used the Internet to contact Calvin. It

turned out that following his hike in Jizeu he had taken a shared

taxi and reached Dushanbe a day ahead of us. He was still with the

French girls. They were about to leave for the north but Calvin

stayed another day because of me. That night, over dinner, we made

plans for the next part of our trip. We were determined to do a

three-day hike in the lakes region of the Zerafshan Valley. Aurelie

who didn't like strenuous activities decided to pass. So once again

it was only Calvin and me, the open road ahead of us.

|

| In the Capital |

|

| Flowery Park |

|

| King Somoli Statue |

|

| Main Street |

|

| Palace of Nations |

Afghanistan

In the south of Tajikistan it was possible to cross into Afghanistan, and for most Westerners getting a visa wasn't

difficult. Permits came at extra cost and they weren't available for many parts of the country. It goes without saying that in Afghanistan safety was an issue. For example, when we were in Tajikistan we heard that the Taliban had become active again opposite the border. While

in Murgab we even saw someone who looked like a Taliban soldier. The

dark faced, bearded man had on a checkered red and white turban, a

loose vest, faded khakis and military boots. He came to our hotel

restaurant late at night and sat in a corner with another shady

figure, a Russian type dressed in military fatigues. The two spoke at

length in hushed voices, and if any glance veered in their direction,

they met it with angry eyes. Perhaps the men were talking about

sports or women. Or they might've been discussing a drug deal.

Afghanistan is the world's largest opium producer and truck loads of heroin

move outside the country via the Pamir Highway. Or it could be the

men were up to something more sinister, maybe an assassination or

terrorist plot. Whatever it was, I didn't stay around long enough to

find out. That next morning I left in the shared taxi with Calvin and

the others.

A

ways south from Murgab the Afghan-Tajik border ran east-west for 1,300km. I covered around half that distance. The journey started in the

shared taxi and continued later while I hitchhiked. Because the roads

we took paralleled the river between the two countries, I was never

more than 200m away. For seven days, to my left all I saw was

Afghanistan. I could best describe the terrain as an endless line of

mountains with villages in the places that arable land allowed

for farming. In some areas the people had no vehicle access. The only

way in or out was on narrow footpaths. Apart from being less

developed it didn't look any different from the Tajik side. The

people were the same too, and as I'd later learn, more ethnic Tajiks

lived on that side of the border than in Tajikistan. But they weren't

the dominant group in Afghanistan. That title belonged to the

Pashtuns. A tribal people notoriously protective of their land, the

Pashtuns had never submitted to a foreign power. They were also

renowned for their hospitality and openness. A shame I didn't have

the chance too meet any. The closest I came was an encounter with an

Afghan man who ran a guesthouse in the Wakan Valley. Because his

father had immigrated from Afghanistan, the son still retained some

Afghan traditions. His wife also made one of the better home cooked

meals I ate in Tajikistan. It was a kind of potato porridge with

carrot and tomato. All the ingredients were fresh too, having come

from the guesthouse garden.

As

we continued onward, ever present Afghanistan became an obsession for

me. I kept thinking at some point I might be able to set foot in the

country. I simply needed to cross the river standing in the way.

Eventually an opportunity presented itself. It began when Ada and

Matilde wanted to take a dip in the River Pyanj. Our driver, Musa,

obliged. He stopped the Pajero at a spot where the water appeared

calm. After we went in, I noticed the river was also quite shallow.

Without much hesitation I made my way towards the Afghan shore.

Unfortunately, 20m from the other side, the river deepened and rose

past my waist. Meanwhile a strong current pulled at my legs. I now

had a decision to make. Across the river only rocks and little shrubs

awaited me, yet I so badly wanted to keep going. However, if I

advanced further the water might drag me under. In retrospect the

right choice seems obvious. I should've turned back round and

returned to the Tajik shore. And that's what I did. But I needed

several minutes before I could give up on my dream of reaching

Afghanistan. When I dried off and hopped back into the taxi, we left

the spot. As I'd feared, I never got another chance to cross over. I

guess some things aren't meant to be.

|

| Stefan Poses Across from Border |

|

| Afghanistan on Left, Tajikistan on Right |

|

| Guesthouse Family |

|

| Only a River Away |

Central

Asian Cuisine

One

of the greater joys of travel is trying new foods, and among the

places I've visited, Thailand, Malaysia, Korea and China have had

exceptional cuisine. Other countries such as Myanmar, Bangladesh and

Cambodia left much to be desired. There were also those countries

with average food. India comes to mind. Some dishes were outright

amazing, but half the time I feared I'd get sick. The sanitation was

that poor. As for the central asian countries, they too fit more or

less into the middle of the culinary scale. Almost everything had

tomato, potato and onion. But a few dishes did stand out. The best

was boso lagman. Consisting of fried noodles and vegetables,

the dish came originally from the Uyghur region of western China. It

was a favorite of Calvin's as well. And most foreigners I met expressed a liking for manti too, something similar to boiled

Chinese dumplings, only larger.

Over time I came to like the standard Central Asian dishes borcht

and pilaf as well , though I can't say they were anything to rave about. Borcht was

a soup made of beetroot and potato, and pilaf contained seasoned rice, diced vegetables and

meat. I should add that the restaurants in bigger cities offered

Western food too. For example, fast food type places had hamburgers

and hotdogs. In Kyrgyzstan the meat inside the burgers was cut from a rotisserie spit, and oddly, the food didn't come with fries. Tajik restaurants had burgers with patties and fries, yet In spite of this, I didn't enjoy them. One in particular tasted so awful I managed only two bites. The meat smelled farty, the cheese was hard, and the bun stale. And I don't

even know what the hell type of sauce they put in it. The pizzas I

tried in Tajikistan didn't taste great either. But draw any conclusions based on only a few meals. Besides, not all the food was bad.

The shawarmas (kebab meat wrap) in Dushanbe were the best I had

in Central Asia. And the local fruit was delicious. The grapes and

strawberries at one bazaar went for only about $0.35 a kilogram. I

also bought apples, apricots, watermelon, cantaloupe, pears, peaches and

nectarines. What I didn't get were bananas. Imported from abroad,

they cost a fortune, selling at places for almost a dollar a piece.

Another

interesting thing to eat was a Tajik dish called kurutob. The

food came in a large clay bowl intended for more than one person. The

contents were diced vegetables, a sour yogurt sauce, and chunks of

bread. I found it delightful both times I tried it. But the taste

aside, the dish was a bit unusual because the bread was mixed in with

the food. With every other meal it came served separate. The most

popular variety of bread in the region was a big circular type with elevated

edges, kind of like a fat pizza crust. This bread often had a design

of small interlocking circles on the surface made by poking

small holes into the dough before baking it. At guesthouses, jam and

butter came included. Tea too was brought out for every meal. The two

main types were green and black. In Tajikistan local custom dictated

that the first cup go back into the pot. As for sugar, people added

heaps wherever I went. In some homes the sugar looked like orange

quartz. The people broke off pieces and let it dissolve in their

cups. I never used any. I prefer my tea straight, same as my coffee.

|

| Boso Lagman |

|

| Pelimen Soup |

|

| Chicken Kebab |

|

| Cafeteria Style Food |

|

| Kurutob |

Lakes

Region

North

of Dushanbe, towards Tajikistan's other large city of Khojand, lied

the large Zerafshan Valley. It ran into neighboring Uzbekistan and

was home to mountain lakes and peaks of over 5000m. Calvin and I went

to the eastern entry point, a town called Sarvoda. By now the end of

August had arrived. The hiking season too was over and the weather

had become unpredictable. Rain could come at any time. Still

determined to do our hike, Calvin and I hired a taxi to take us high

into the mountains. A light drizzle and clouds shrouded the area in

grey. After a bit of hiking we first arrived at the Alaudin Lakes.

They were perhaps the clearest lakes I'd seen in my life. And more

astounding were their colors. In the shallows algae formed a web of

green while the centers had the deep blue of topaz. However, the poor

weather prevented us from seeing the lakes at their best. We made

camp on the shore and hoped by morning the sky would clear.

The hour

was still early. To pass the time we watched videos inside the tent

on Calvin's Samsung tablet. He'd gotten me into Avatar: The Last

Airbender, an animated series that takes place in a medieval

fantasy world where people can control the elements. Years before I'd

been a big fan of Japanese animation, and Avatar, though an

American show, emulated the style very well. The series felt like an

anime not only in style, but also tone and humor. Because Calvin and

I had already spent many nights in the tent, we'd also watched other

shows and films. It was quite odd. We'd done camping all over, often

miles from any town, and instead of enjoying the silence of nature or

engaging in thoughtful conversation, we preferred to zone out with

our digital devices once inside the tent.

For

the second day of our hike, we awoke to rain and discovered that a herd of cows had invaded our spot along the water. The animals had no shame.

They tore up grass and shat where they stood. We packed up the tent

and made for Alaudin Pass. The rain subsided on the way up, but by

then I was too far from the lake to take nice pictures. The larger

mountains also remained covered by clouds. So in spite of being in an

incredibly picturesque setting I failed to get any good photos. Later

we reached the 3860m pass and continued on the trail past Mt.

Chimtarga and its glacier, both still hidden by clouds. The hike went

okay for a while until heavy wind and rain set in. We'd planned to

set up camp at another lake called Kulikalon which was still hours

away. I didn't own waterproof gear like Calvin and had to endure the

cold and wetness in only a wool sweater. Eventually we came to the

lake's shore. The spot we chose for the tent was on a small rise

surrounded by rocks, bushes and other natural scenery, but again, the

weather ruined the atmosphere. Our tent wasn't entirely waterproof

either. Rain leaked in from the sides and persisted well after dark.

|

| Sarvoda Town |

|

| One Alaudin Lake |

|

| Green Algae |

|

| From a Distance |

|

| Sheep Grazing |

The

next morning the weather was still poor. We needed to hike out of the

mountains to a village where we could find a guesthouse. Along the way

we ran into a group of Tajik students on a trip to Kulikalon Lake.

They asked to take group pictures and we posed for a few. Then on we

walked until the trail linked up with a dirt road. A few simple homes

now lined the river valley we passed through. At one, a woman waved

us over. She gave us bread and fruit while her children looked on

with curious eyes. The kids also each drank from my water bottle.

Seeing them put their tongues in the opening made me not want to have

anymore, this in spite of being very thirsty later. When the family dog came the kids mounted and choked it. I'd have have snapped them in the faces. Before departing

we offered the woman some money for the food. She didn't seem to want

it, but the children stepped forward and gladly took the cash.

Back

at the road a guy stopped his car and said his family had a guesthouse in the

village of Artush. He quoted a reasonable price and offered to give

us a lift the rest of the way. Storm clouds were again brewing on the

horizon, so we agreed, and off we went in his small, beat up vehicle.

The patter of rain soon sounded as the man drove us past farms

and donkeys en route to the house. It turned out to belong to his

sister. We arrived early in the day and she served us lunch on top of

the usual dinner included in a stay. At the table her son took an

immediate interest in us. He kept coming into our room and later

wanted to play checkers. I gave it a go. The rules were different

than the American version and I figured them out too late to beat him. Calvin avenged me. The boy requested a rematch

and won the second time. He didn't realize Calvin had lost on

purpose.

Our

last stop in Tajikistan was Khojand, the country's second largest

city. We stayed one night in order to see the bazaar and mosque complex, then crossed into Kyrgyzstan. There ended our

adventures in Tajikistan. In total we spent three weeks in the

country, having made a loop south from the Kyrgyz city of Osh and

then back. As for my final impressions of Tajikistan, I'd say it

wasn't so easy a place to travel without spending a lot of money.

Accommodation was pricey as was transport outside the main cities.

I'd found this odd considering the low standard of living. But I

should have expected it. Tourism was relatively new to the country

and rural areas lacked infrastructure. So to go to remote places and

get things done cost a fair amount. However, it was in the difficult to reach areas that the people showed the most kindness. Several times they invited me to stay at their home. Too bad the short notice made it difficult for me to change my plans. More often than not I had to decline.

|

| Khojand Baazar |