Progressive State

A former Belgian

colony, the country of Rwanda has only recently shifted from French to using

more English as part of its ongoing integration into the larger East Africa

cultural sphere. Compared to its neighbors it is the most developed country in

the region. A beacon of order and progress, the local people refer to home as

the Singapore of Africa. But as in Singapore, moving forward has come at a

cost. The government imposes strict laws regarding public conduct, and the more

money people earn the more obsessed they

become over status and privilege. Security is also a problem. Internal strife

has torn apart both the Democratic Republic of Congo to the west and Burundi to

the south. Refugees continue coming across the border, a stark change from when

Rwandans had fled into those countries to escape their own civil war some 20

years before. In Africa a country can abruptly become undone in the turn of a

few days. But somehow Rwandan president Kagame has held his country together

and allowed it to flourish economically. Many people have told me that now its Africa's

time. After centuries of exploitation and economic stagnation the continent is

on the verge of rising up to claim its due place on the global scene. Rwanda

may be small and lacking in natural resources, but it will without a doubt be

one of the countries to lead the way.

|

| Rwandan Flag |

Genocide

For most Westerners,

when the name Rwanda comes to mind, it evokes vague recollections of the 1994

genocide between Tutsis and Hutus, a conflict that by some estimates left as

many as a million dead. The Rwanda Genocide Memorial in the capital of Kigali

was erected beside a mass grave of the victims. The site recounts the history

of division between the Hutus and Tutsis, along with the eventual tragedy that

befell the country. From what I gathered the two groups originally had some

ethnic differences but were later categorized as social castes, with the Tutsis

being the more privileged one. Then, during the Belgian colonial era, the

governing body drew a clear distinction classifying Tutsis as

those families which owned 10 or more cows, and all others Hutus. The Belgians

favored the Tutsis in society which caused resentment among the poorer Hutus.

In 1962 after the Belgians left the Tutsis held most positions in government.

In time the numerically superior Hutus challenged them and this inevitably led

to civil conflict.

In 1993 the situation

took a turn for the worst. In Burundi, the country south of Rwanda, chaos broke

out between Hutus and Tutsis, and some 200,000 died. This should have been a

warning to the UN and other security forces in the region. But when the same

thing happened in Rwanda a year later, they stood by unprepared to act. The

country was already at war between Tutsis and Hutus. Matters then escalated

with the downing of an airplane carrying the Burundi president and Rwandan Hutu

leader Habyarimana. The Hutus blamed the Tutsis for the attack and Hutu general

Bagosora called for action. He instituted a plan of ethnic cleansing, and using

military force, began to round up Tutsis. But it was propaganda spread over the

radio that caused most the damage. The Hutu leadership incited the Hutu masses

to violently turn on their Tutsi neighbors. In villages around the country men

soon used machetes, bamboo spears and other makeshift weapons to butcher any

known Tutsi. To prevent escape, checkpoints popped up on roadways where armed

Hutus asked for identification. At the time a Rwandan ID showed whether a

person was Hutu or Tutsi. The latter were killed outright.

|

| Inside Memorial |

|

| Human Skulls |

|

| Display |

|

| Photos of Victims |

The carnage lasted for

about 100 days and an estimated 90% of the Tutsi population was murdered. Often

it was friend who killed friend. And in the case of intermarriage, Hutus had to

kill their Tutsi spouses. If a Hutu woman had had children with a Tutsi man,

she was forced to kill her children the same. Known HIV positive men then raped

the woman to further punish her for having married a Tutsi. No one was exempt.

A wave of horror swept across the land, one that people later likened to Armageddon.

Little surprise that Tutsis sought refuge in the church. But even pastors

turned on their congregations allowing helpless people to be brutally

slaughtered in the Lord's house. It was carnage of the highest degree.

In spite of deeply seeded hatreds, imagine that during

this period many Hutus were not inclined to murder their neighbors, but in such

a climate of fear, they did not have the

courage to do otherwise. It's a hard truth to accept. People would like to

think they'd do the right thing under terrible duress, but no one can say for

sure how they'd react until confronted by the unthinkable. In the case of the

Rwandan genocide, it took true character, and only in rare cases did Hutus

stand up for Tutsis. Some Hutus hid and fed refugees until the bloodshed was

over. In other instances they helped them to escape across the border into

Congo or Uganda. If caught, such defiance was punished by death. Thus, moderate

Hutus too numbered among the victims.

The killing ended when

Kagame, the leader of the Tutsi RPF (Rwandan Patriotic Front), subdued Hutu

military forces. Once the war was lost many Hutus fled the country for fear of

reprisals. The French, who had for years supported the Hutus, allowed the worst

perpetrators to flee the country. As for the RPF army, soldiers returned to

villages to find family and friends dead, the corpses sometimes still warm. A

number of these soldiers shot the Hutus they'd suspected of carrying out the

murders. Kagame did not condone

retribution of this kind, and to set an example, he executed soldiers caught

killing non-combatants. In this manner order was maintained. Then, once the

country was secure, Kagame began the process of rebuilding a torn nation, and after

that, the even more difficult process of reconciliation.

When I went to the

memorial in Kigali, I took my time reading every display, and watched the many

videos. It was a tense experience. In the videos, survivors described in vivid

detail how loved ones were raped, tortured and butchered before their very

eyes. Other times it was displays that presented morbid stories of infants

being hacked to pieces in their mothers' arms. If there's one thing I can't

stomach, its abuse towards children. Seeing photos of the victims, once smiling

and happy, I felt disgust in my heart. The senseless murder of innocents was of

a magnitude of order that has made me wonder time and again if people are

innately evil, for what had happened in Rwanda really was humanity at its

worst. To not repeat the same tragedy, the world should never forget. Rwanda

certainly won't. Every April the country has a public week of mourning to

remember those lost.

|

| Mass Grave Site |

|

| Frog in Garden |

Book

What I write here is in

effect a blog. I have shared my interests and experiences while traveling and living

abroad. A blog has also let me express my thoughts to friends and family

wherever they might be. But above that I write for myself. When I was a child I

enjoyed reading all types of books. I devoured novel after novel, and I admired

the authors who'd crafted them. As I grew older I hoped I too could write a

book of my own. It never mattered to me if someone would publish it or not. I only

wanted to have something physical to show for. So I wrote pages and pages of material. Yet regardless of how much

effort I put in, I couldn't complete any book I'd started. I didn't stop

writing though. Maybe I didn't have a big story in me but that didn't mean I

couldn't type out something else. A journal for example.

In 2007 something crazy

happened. I got cancer. First came surgery and then began the chemo. Because I

was in Japan and had insurance they kept me in the hospital for two weeks for

each of three rounds. It gave me time to think. I considered the things I had

done, and those I'd wanted to do but never did. Creating a book was one of them.

So I started again with renewed vigor. I wrote about my experience with cancer.

But I had the same problem as before. I'm not a good writer. I lack the ability

to formulate a strong narrative. Like so many other would-be authors my stories

jump around, become dull in parts, and in the end don't hold together. It's

also about discipline. I couldn't keep at it--iron out the wrinkles so to

speak. Sad as it was, I failed yet again to complete a book. But I did do other

things. I travelled extensively. I became more socially active, made new

friends, joined a theater group, went out to take photos whenever I could. I

tried my best to make life more worth the living. And it went well. I did my

follow up tests and the cancer never returned. In the meantime I had several

good years in Japan. Then I left.

I didn't think to try

writing a book again. Not even after I'd started what would become this one.

But here it is. A work still in progress. For now it remains a blog. But I'm

putting the book together concurrently via a website called blurb.com. They operate as a vanity press. You provide the content and

pay the money, and blurb creates a beautifully bound, professional quality

product. What's great too is that the book is printed in color and can contain

photo quality pictures. Another dozen such similar sites exist. The difference

with blurb is that the site has a downloadable editing program. That way I

could install it and on my laptop and put my book together offline.

|

| Artsy Cards |

Reconciliation

In 1944 a Jewish man by

the name of Raphael Lemkin created the term genocide to describe what Nazi Germany had done to

the Jews before and during WWII. In the years since, large scale genocide has

not been so common in the world. So it was of great misfortune that one took

place in Rwanda. In the aftermath the country was in utter chaos. There were

far too many dead to bury at once. In the streets stray dogs ate the bodies

where they lie, and the animals had to later be put down because they'd

developed an appetite for human flesh. Other people were dumped in mass graves,

never to be identified, no one left to mourn them. As for the survivors, they

searched desperately for family who might still be alive. It was a long and

trying process of small community networks. But more often than not there

weren't any joyous reunions to be had. The children had it the worst. 90% of

those alive at the end of the genocide had either been exposed to, or subjected

to violence. Now adults, these people still carry the emotional scars of a time

they will never be able to forget.

After Kagame had

defeated the Hutu militants in Rwanda, he had a choice--revenge or

reconciliation. He went with the second. But it was a delicate situation. How

could he reconcile with the Hutus who had only a short time before murdered

most the Tutsis in the country? Kagame began by dealing harshly with those who

had orchestrated the genocide. But other men who had become swept up in the

violence and killed under orders were brought to stand trial before local committees.

If convicted, the perpetrator was given a choice. He could admit his to his

crime and then ask forgiveness from the victims. In the event he did his

sentence was reduced, and rather than serving time in prison, the man could

spend his sentence doing civil work to help rebuild the country. It was a start

in the right direction. But Kagame did not stop there. He also eliminated the

distinction between Hutus and Tutsis, declaring that the people of Rwanda were

now one people--Rwandans.

The Hutus that had fled

into Congo, however we're still a problem. They reorganized and were intent on

opposing the RPF government. Kagame, with US backing, hunted them down in the

deep Congo jungle. But the rebels were too numerous to contain. Sometimes they

crossed the Rwandan border and raided villages. In one incident in 1997 they

went into a school and demanded that everyone separate into Hutus and Tutsi.

The students, only 12 year old boys, refused, saying, "We are all

Rwandans!" The soldiers tossed a grenade as a result, killing many

indiscriminately. But those who died did not do so in vain. Their example of

courage and solidarity sent a message across the country, one that inspired

others to set aside their hatred and differences. The situation has only improved

since then. If only the same could be said for elsewhere, in Congo for example.

Unfortunately, for that country, the presence of Rwandan militants precipitated

the First and Second Congo Wars, involving at one time or another, soldiers

from Rwanda, Uganda, Burundi, Angola, Zimbabwe, Namibia, Chad and Sudan. The

two wars have since become the world's bloodiest conflicts since WWII. To this

day insecurity plagues the land and it was for that reason I did not visit.

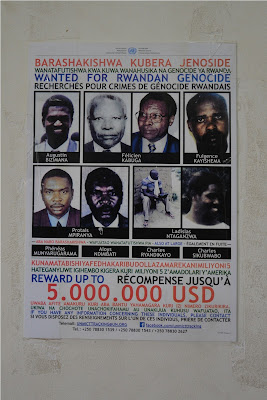

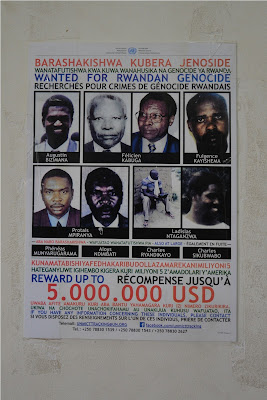

|

| Genocide Criminals |

Kigali

Topographically, Rwanda

is dominated by hills and is not the place to build big cities. Kigali is the

largest. To go from one part of the city to another required a lot of ups and

downs. The most convenient mode of transportation was on a motorcycle taxi.

Unlike elsewhere in Africa, the drivers were required to register with a

company and use a helmet. They also had a helmet for passengers and carried

only one at a time. This was an example of the type of order that Kagame had

instituted in his long tenure as president. Throwing trash in the streets came

with consequences too. And crime was rare because every 100m or so, armed

soldiers stood watch 24/7 and communicated with others in the area by radio.

Then plain clothed police roamed the streets mixed in with pedestrians, ever

watchful. For a city of its size, Kigali was likely the most secure metropolis

on the continent. It was also eerily quiet at night. The place didn't have a

curfew, but aside from in a few nightlife spots, there was hardly anyone on the

streets after 10 o'clock.

Gati had a friend from

France who was living in Kigali. The woman, Barbara, was studying to teach

French as a second language. She had only recently found a room at a shared

house a ways outside the city center. I was thinking it would be a simple set

up, but when we pulled up front by motorcycle taxi, the house was a big white

mansion. Well, not quite. It had only 5 rooms. Yet with its colonnaded walls

and large yard I couldn't be blamed for my first impression. Inside the house

lived a mix of Africans and Westerners. One guy, Vicky, dedicated himself to

painting. He was from Rwanda and had been a boy when then the genocide happened.

Most his family had died and he'd soon became a solider, using a rifle to kill,

and doing it at an age before most men require their first shave. But I'd have

guessed it by looking at him. He was a

gentle, friendly guy who shared everything without a second thought. It's

strange how life takes its twists and turns like that.

Barbara was a good

host. To repay her kindness I cooked dinner so that we could sit

down and have a nice meal together--me, Gati, Barbara, and her Rwandan boyfriend whose

name was Ngenzy. When I'd dropped by the local market earlier, I took in the

fine selection of vegetables, beans, rice and fruit. My eyes grew wide at the

sight of the avocados. They were big, green, and cheap. Two ripe ones was

all I needed to later fill a bowl with creamy guacamole. Another French friend

named Bruno invited us over another night for dinner. He had married a local

and she'd recently bore him a son. Bruno was in love with Africa. He'd had lived in

Burundi two years prior and even stayed a few months into that country's

political collapse in order to finish a project. And going back a year more,

he'd spent six months in a village in the Kalahari desert of Namibia. Oh the

stories he told me over beers, of how a black mamba had attacked his moving

jeep, or how he'd eaten elephant and giraffe meat with the tribesmen, the leftovers

of the game hunts carried out by wealth foreigners.

The last thing Gati and

I did in the city was climb Mt. Kigali. More of a large hill than a mountain,

it loomed over the southern extreme of the capital, and opposite, gave way to

villages and countryside. At the top was a horse ranch, a rarity in the region.

Gati liked horses, but to ride one cost too much for her. So we ventured a

little further and found a type of restaurant bar known for its BBQ rabbit. It

was a Sunday, and a young group of Rwandans were drinking beer at a table. They

invited us over and said they'd been partying since the night before. One of

the ladies at the tables sat toppled over her boyfriend. She awoke when the food

came. The four of them had ordered a plate of rabbit and shared it with us. I

made due with a leg. It was tough and stringy, but delicious nonetheless.

Before leaving I went to see the rabbits that were still alive. There were

perhaps 20 and a man was feeding them grass. Rabbit meat was uncommon in

Rwanda, and yet these rabbits were about to become it. Poor little animals I

thought. They'd never see the knife coming until it was too late. How

hypocritical of me though to pity them. I'd just eaten one.

|

| Downtown Kigali |

|

| City Suburbs |

|

| Local Brew |

|

| Barbara's Home |

|

| Out for Fun |

|

| Lovely Avocados |

|

| Vicky |

|

| From Mt. Kigali |

Lake Kivu

After Kigali we went to

the western extreme of the country where most the border ran along a deep water

lake called Kivu. A few towns lined the shore. We first visited Kibuye. Built

into green hills that fed into the water, Kibuye was an incredibly beautiful

place. The hostel we stayed at, St Jean's, stood atop a peninsula with excellent views. There we met two medical students who were doing an

internship at a medical center in the city of Huye. The guy was from Vermont

and the woman from Amsterdam. The next day we shared a boat on the lake. Our

guide took us to Napoleon Island famous for its colony of fruit bats. He led us

up a hill and rambled down below into the bush. When he was low enough he

clapped his hounds loudly and startled bats rose into the sky. Thousands and

thousands of them circling in the sky. They were the large variety with the

head of a dog, something like that of a Jack Russell Terrier. I took loads of

photos before they settled back into the tree tops.

Kibuye, for all its

majesty, didn't have much to do besides soak in the scenery. So we soon took a

bus north to another town called Gisenyi. It was a public bus that quickly became

packed with locals. The woman next to me had a little boy flopping his head

over her arm. The road wound through a dirt road in the hills and the movement

made the boy sick. He threw up on my foot and backpack. The mother apologized

and tried to wipe it off with a handkerchief. Onward the bus went, over the

bumpy road, up and down. The scenery was stunning, endless green hills with

small villages scattered throughout. But the ride was slow going, painfully

slow. It took seven hours to transverse the 110km to Gisenyi. I was so happy to

reach the city I could have kissed the dusty sidewalk once I'd gotten off. But

our priority was to find a lodge. We settled on an establishment called the

Africana. After that we had an early dinner. I was biting into a forkfull of

beans when I crunched down on something hard. It was a small rock and it

chipped one of my upper molars.

I needed to get the tooth fixed and worried the treatment would be subpar

considering Gisenyi wasn't so big a place. But I found a good dentist and he

went to work with his pointy instruments and loud drill. I'd had a cavity in

the same spot and he scraped it out before rebuilding the tooth. When the work

was done I walked out the office tense all over. I won’t deny how much I hate visits to the dentist. It’s up there alongside a swift kick to the balls as one of my least

favorite things. Anyhow, Gati and I meandered over a half kilometer to the

border crossing into Congo. On the other side was a town called Goma. It was

one of the more secure places in the country and we saw military planes flying

in endlessly, their flight path crossing over the lake. At the border I found a

currency exchange kiosk and traded for Congo francs to add to my money

collection. Interestingly, one of the bills showed a picture of men digging for

diamonds--blood diamonds to be sure. Odd that the government would want to

promote the industry on its currency.

Part of the lakeshore

in Gisenyi had manmade beaches. I'd heard the water contained some kind of

parasite and did not go for a swim. Trapped beneath the lake

was also a large amount of carbon dioxide that might at any moment erupt (but

never has) to the surface and suffocate all animals and people in the area.

Still, it was pleasant to sit near the shore and enjoy the breeze while little

waves lapped at the sand. I was lying back on the grass when a young local guy

came and struck up a conversation. He said his name was Antony and he wanted to

practice his English. So we talked politics and tourism. I learned that in Rwanda

it was difficult to start up a business because of high tax rates. But over in

Congo enterprise was a simpler matter, so in spite of the country's

instability, many foreigners still couldn't resist going in to make a quick

profit. Later Gati and I had dinner at a lakeside restaurant, and taxes and

all, the business seemed to be managing well. The joint offered beer and simple

food items. Gati and I ordered kebabs with French fries, an unhealthy yet quick

go to meal in East Africa. I sinfully washed it down with a bottle of Coca

Cola.

|

| Lake View |

|

| At Hostel |

|

| Boat Ride |

|

| Looking Down |

|

| Local Church |

|

| Gisenyi Mosque |

|

| Border Crossing |

Volcanic

The eastern part of

Africa is geologically split into tectonic plates that 35 million years

created the Great Rift Valley. It is divided into two branches, the western part having thrust up mountains that mark the borders between Rwanda, Uganda

and Congo. In Rwanda the mountains make up the Virunga Range, and at the base

we visited the city of Musanze. I'd lined up a Couchsurfing host beforehand for

the first time since arriving in Africa. The man's name was Hormisdas, and his

wife Modeste. They were very welcoming. As usual I wanted to cook them some

food. But because Modeste said she'd do dinner I prepared only guacamole and

served it with chapati bread as an appetizer. Hormisdas had invited other

friends as well, a volunteer worker from Germany and her visiting parents. The

father was a former journalist and he rambled on and on about the refugee

crisis in Europe. That lead to a deep political conversation that exposed my

ignorance regarding the German government. I hadn't even know the name of their current chancellor. Yet Hormisdas understood very well the politics. It never ceased to

amaze me, the knowledge possessed by the Africans I met. People from the

outside look at the continent as some kind of backwater, a huge expanse of

ignorant uncultured types. From what I'd seen it couldn't be further from the

truth.

At first Gati and I

were thinking of climbing a volcano. But the cost proved too high. The other attraction in the area was to see the highland gorillas. That was even more

money. $700 for a one day outing. So we settled on two side trips outside of

town. The first was to a tea plantation. We got off the local bus and walked

right into the fields. Locals were hard at work picking and sorting leaves. They looked at us with

mild curiosity, probably wondering why foreigners had come to their place of

labor. If they'd spoken English I'd have told them the reason. I wanted to take

pictures of the green expanse of plants. The plantation sat flat in a valley

that extended out of sight. Several children followed us as we went deeper and

deeper into the valley. The female workers had baskets on their head or back.

They also wore a colorful wrap called an entege, the traditional women's wear

of Rwanda. I wanted to take pictures of them too, but they weren't having it.

The whole time I'd traveled in Africa the locals did not like me pointing my

camera at them. The exception was if I knew the person well. Then they didn't

seem to mind.

Our last day in Musanze

we visited the nearby twin lakes. They were also in an area few foreigners went

to. We walked from the main road onto a dirt track that lead past village after

village. The locals here, like in Musanze, we're very friendly. Though they

didn't speak English everyone greeted us and smiled without fail. As for the

kids, they of course pointed and said "Muzungu." I tried counting how

many times I heard the word but lost track after 20. When we got to the lake it

was at the edge of a large village which we had to pass through on an adjacent

trail. This was a very rural area. People grew corn and other foodstuff on

scraggly earth dotted with volcanic rock, and the houses didn't look like much.

Children followed Gati and me. Some of them spoke to us, using random English

words. It wasn't much communication-wise, but they were trying and I was happy

to humor them with responses. Once they understood what we wanted to see, they

guided us to a small port on the lakeshore. The landscape lacked the impressive look of Lake Kivu, but it was

still a joy to gaze out over the water after such a long walk.

Gati and I both agreed

that Musanze was our favorite place in Rwanda. The people convinced us of it.

When we returned to the village center we wanted to return from there to the

main road by motorcycle taxi. Only one bike was available though. So the driver

called his friend to come, and we sat and waited. It ended up taking forever.

In the meantime a growing group of locals formed a tight circle around us. Most

of them were children but some older people stopped too. Being the center of

attention I felt I had to do something. I showed them my camera, then took out

a map I had of Rwanda. Gati noticed that a little girl was wearing a San Diego

Zoo t-shirt. I snapped a picture of her, and she felt so singled out, she

almost cried. Thankfully, one of the locals could speak English, and he

explained why I'd wanted the photo. The other driver finally arrived and we

hopped on the two bikes to return to Musanze. From there we headed back to

Kigali, but before leaving I printed a picture I'd taken earlier of Hormisdas

and Modeste. You know, it's those little things that show gratitude for a CS

host's hospitality.

|

| Modeste |

|

| Church and Graves |

|

| Out to Pick Tea |

|

| Glorious Tea |

|

| Volcanoes |

|

| Boys Pose |

|

| For Sale |

|

| Gati on Motorcycle Taxi |

|

| Boat on Water |

Wrap Up

We only spent a little

over two weeks in Rwanda. Perhaps the country warranted more time, but in many

respects it was similar to Uganda, and we decided we should continue our

travels to another place. We were fortunate to have a friend like Barbara in

Kigali. She welcomed us into her home during our long journey, and staying

there, even if only for a few days, gave us the opportunity to recharge. I was

also lucky to be with Gati while on the road. And from her perspective, she was fulfilling a

dream of visiting Africa, something that would have been difficult on her own

as a woman.

|

| Walking on Stilts |

No comments:

Post a Comment